The Vietnam War Memorial: How Maya Lin Revolutionized Memorial Design

Creating The Memorial

In November of 1980, the open competition for a Vietnam War memorial was officially announced. The rules required submitted designs to be anonymous and non-political while honoring the fallen veterans.

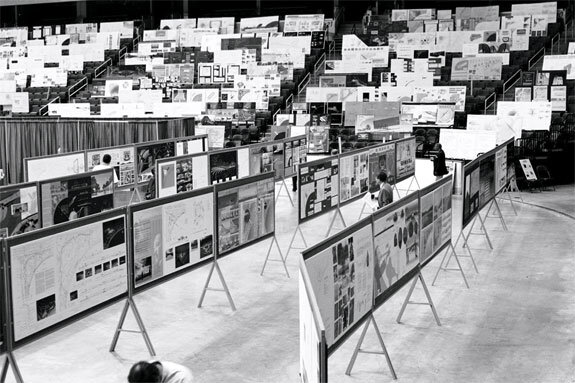

The Design Competition: the entries and the jury deliberating.

Photo from The Attic.

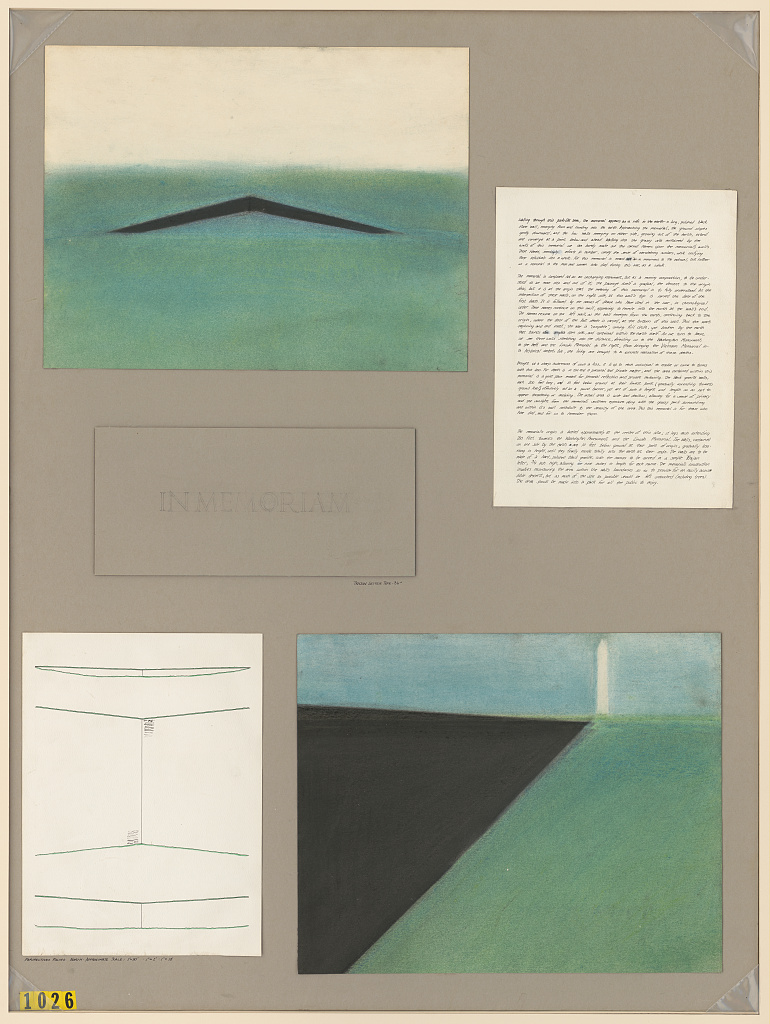

Photo from Competitions.org.

“From the very beginning, I often wondered, if it had not been an anonymous entry 1026 but rather an entry by Maya Lin, would I have been selected?”

~ Maya Lin

At Yale, in a class about funerary architecture, students were assigned to design a memorial for the competition. The most captivating submission was that of 20-year-old Maya Lin, whose design consisted of a horizontal V, with a vertex below ground. Lin’s submission stood out from the others as being more simple and delicate, with an emphasis on loss instead of heroism.

Photo from Library of Congress.

Lin’s entry, including pastel sketches and an essay.

“I imagined taking a knife and cutting into the earth, opening it up, and initial violence and pain that in time would heal. The grass would grow back, but the initial cut would remain a pure flat surface in the earth with a polished mirrored surface, much like the surface of a geode when you cut it and polish the edge.”

~ Maya Lin

“The winning design is a great one. We believe it should be built as designed. It reflects the precise nature of the site designated by Congress. It is aligned beautifully with the Lincoln Memorial and Washington Monument… a unique horizontal design in a city full of vertical ‘statements.’ It uses natural forms of earth and minerals, without attempting to dominate the site. It invites contemplation and a feeling of reconciliation. The design, by creating a place of utter simplicity and serenity, is a work of art that will survive the test of time.”

~ Grady Clay, jury chairman of the competition

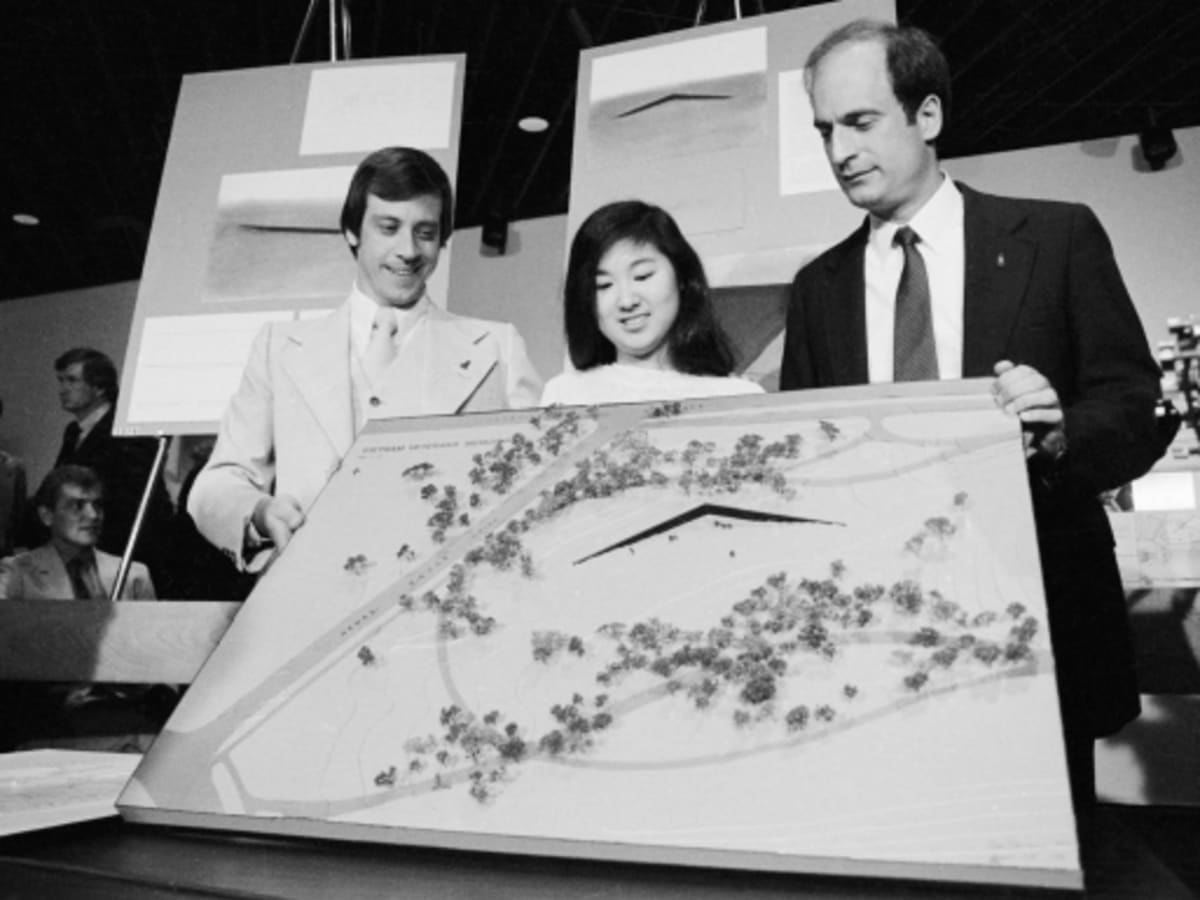

Photo from Yale Alumni Magazine.

Photo by Bettmann, Getty Images.

Lin and her winning entry, with Project Director Bob Doubek and Jan Scruggs.

When the winner of over 1,400 submissions was revealed—a young, Asian-American woman, an amateur designer—people were shocked. Most architects supported her vision, but others attacked her design for being too abstract and lacking the conventional symbols of heroism, such as American flags and sculptures of soldiers. As time went on, opposition to Lin’s design grew, until the Fine Arts Commission intervened and held a public hearing in October of 1982. Despite Lin’s efforts to defend her original vision, a more “patriotic” design was forcibly added nearby to appease her critics: the bronze statue The Three Servicemen by prominent sculptor Frederick Hart.

Photo by Robert W. Doubek.

Photo by Robert W. Doubek.

Photo by Vietnam Veterans Memorial Fund.

The memorial's construction, 1982, and The Three Servicemen statue, added 1984.

However, Lin successfully fought to keep the veterans’ names in chronological order rather than alphabetical, to use black granite, to have razor-thin walls, to minimize the number of heroic inscriptions—to ultimately preserve the introspective, personal nature of her design.